Making Kate Bush: The Dreaming

By Matthew Lindsay | March 22, 2022

She called The Dreaming her “mad” album, and Kate Bush’s belated return to the studio with cutting edge Fairlight sampler at the ready, bore fruits of an entirely different kind…

Wuthering Heights had made Kate Bush an instant star, but with Never For Ever, an 80s auteur was born. Co-produced with Jon Kelly, Bush had delved deeper into sonic detail and difficult subjects; it became the first No.1 female studio album, spawning three hit singles (Breathing, Babooshka and Army Dreamers).

Session work for Peter Gabriel 3 had “opened the windows”, introducing her to the Fairlight sampling synth and rhythm boxes. (she was impressed by the ex-Genesis-frontman’s “guts”). But Smash Hits’ readers’ favourite female singer of 1980 was frustrated.

Never For Ever was split between two decades, sprinkled with 80s state-of-the-art seasonings and the deep-70s session sparkle of earlier albums. It was an intoxicating blend; Bush was more satisfied than before. But she still hadn’t accomplished what she wanted. Post-album blues hit; depression, introspection and writer’s block.

In September 1981 she’d tell Record Mirror her writing had required a pattern-breaking “shock”. It came early that year, with Bush spontaneously laying down 20 demos, written on piano to a Roland drum machine, adding her second favourite synth, the touch sensitive “human-sounding” CS-80.

Two works-in-progress, The Dreaming’s title track and Houdini were ideas she’d had on Never For Ever. The new approach was to go “all the way”; be more “experimental and cinematic” than before.

This cutting-edge technology would rub shoulders with the arcane and ethnic, hinted at by the folk and world music she’d played on Paul Gambaccini’s BBC radio show. Another selection, Lennon’s No.9 Dream, reflected a growing Beatles influence. Broadcast December 1980, the month of Lennon’s assassination, much of Bush’s new music seemed cast in the tragedy’s shadow.

She opted to self-produce, (Tony Visconti, who’d written her a Lionheart-inspired fan letter during Bowie’s Lodger, was briefly considered). In a Denmark Street demo studio, drummer Preston Heyman was introduced to Bush’s new methods. Sat In Your Lap’s piano riff reminded him of Dave Brubeck’s Take Five, he played along accordingly. She then removed his cymbals, then his snare.

It morphed into a tom-tom pattern more akin to the Warrior Drums of Burundi (used on Joni Mitchell’s The Hissing Of Summer Lawns). Eager to get the tribal, drum-heavy sound onto tape she headed to Townhouse Studios, specifically it’s ‘stone’ room. This was where engineer Hugh Padgham had created the colossal ‘gated reverb’ drums on PG3 with drummer Phil Collins.

Read more: Top 40 Kate Bush songs

Read more: The Lowdown – Kate Bush

Bush had been equally impressed with In The Air Tonight (a ‘masterpiece’). Padgham worked on Sat In Your Lap, Leave It Open and Get Out Of My House, giving Bush the rhythmic oomph she required, aided by the studio’s Solid State Logic console with its gates and compressors.

A hard, driving core aside (Rainbow’s Jimmy Bain played bass), these tracks weren’t ‘rock’ or ‘normal’ and Padgham was bewildered by Bush’s unorthodoxy. For Heyman, though, it was exactly this “weirdness that we rejoiced in”. For Sat In Your Lap, the drummer and brother Paddy Bush stood ten feet apart, swooshing bamboo sticks (a cracked one stayed in the mix too).

Space was found for one Chinese opera cymbal suspended from a rope, “throttled” periodically by Heyman. Struggling to replicate the demo’s CS80 parts, Buggles’ Geoff Downes supplied a Fairlight brass section (he was busy working at Townhouse on Asia’s debut).

In June 1981 Sat In Your Lap hit the shelves, unveiling Bush’s new direction in a white sleeve, ballet-dunce Bush glancing quizzically at a globe. Inside was a torrent of avant-garde pop; rumbling rhythms, philosophical head-scratching and a startling vocal ferocity.

Bush fretted, initial feedback was dumbstruck silence. But critics raved (“a superb blast of energy”), as did BBC’s Roundtable guest reviewers, Linx’s David Grant, and Rick Wakeman. It climbed to No.11, a year later it sat atop Trevor Horn’s all-time top ten, one of three Bush selections.

Meanwhile, The Dreaming’s sessions had steamed ahead. The in-demand Padgham left for Genesis’ Abacab, replaced by Nick Launay. His CV, including PIL’s The Flowers Of Romance, aligned the young engineer with Bush’s new almost post-punk edge.

With a seemingly limitless budget and new gadgetry, he was a more willing accomplice in what he calls the ‘toy shop’ of Bush’s experiments. Corrugated iron wrapped around drums became ‘canons firing across a valley’ for Leave It Open’s climax. Bass player and then-boyfriend Del Palmer sampled aerosols to replace those forbidden cymbals.

If a song suggested a “flood imagery to be painted in”, everything was attempted. To bring the Australian outback to life on the title track there were smashed marble, crowd noises from the Gosfield Goers, and Percy Edwards’ wildlife impressions.

Supplying the didgeridoo’s circular drone was Rolf Harris, whose 1960 Sun Arise had been The Dreaming’s inspiration. Amid the Fairlight skids and thuds there were real accidents too; Paddy Bush’s bullroarer broke, frantically spun wood dislodged from cord, hitting the studio’s soundproof screen. Bush’s next location was Abbey Road, with engineer Haydn Bendall.

Read more: Kate Bush albums – the complete guide

Read more: Making The Hounds Of Love

Taking up all three studios for Night Of The Swallow, Stuart Elliot’s drums fed from one to the next. For the chorus, a ceilidh band was required. Bill Whelan provided the searing Irish folk arrangement, played by members of his band Planxty and The Chieftans, captured in an all-night Bush-attended Guiness-soaked session at Dublin’s Windmill Lane.

At some point, Bush says “the spontaneity evaporated”. Studio-hopping with an ever-expanding cast, while the songs “kept changing shape” became “hard work”. The endless mind-voyaging from the Outback to the East Asian jungle for Pull Out The Pin required searching for right sonic mise-en-scene.

Bush’s role-playing was intensely demanding, becoming a bank robber, a Vietcong soldier, Mrs. Houdini. Often switching character within one song, her vocals (usually recorded at night), needed an array of effects to distinguish them. She was like an actor-director placing huge demands on herself from either side of the camera.

Conjuring “distorted emotional states” left her drained, even frightened. And through the masks, autobiography flickered, the music’s mad ambition offset by nagging self-doubt, as in There Goes A Tenner: “the sense of adventure is changing to danger”.

The clock ticked, the costs mounted, and EMI grew impatient. Years later Bush told Mojo: “They were going to get me, beat me down and I wasn’t going to have the strength to see it through”. The siege mentality seemed ripped right out of The Dreaming. “A breath of fresh air” came with Paul Hardiman (Wire, Soft Cell), her final engineer/mixer, and along with Palmer, a trusted co-pilot for the album’s long, last stretch.

Moving from Odyssey Studios to Advision in early 1982, these were 15-hour sessions, “digging for jewels in the facility’s windowless bunker”, existing on Chinese takeaways. They put bottomless polystyrene cups on their ears to keep them laser-focused.

It was complete in May 1982. Baffled by this strangely beautiful music, hearing no obvious singles, EMI nearly rejected the album. Ultimately, it was accepted with the same reluctance RCA met Bowie’s Low with. For Bush it was mission accomplished.

She even, finally, liked hearing her own voice. Often “consciously aggressive”, Bush’s themes, ever-darkening since Lionheart with their “grotesque beauty” and “sad humour,” were matched by the sound.

In July the title track was released as a “necessary trailer” It stalled at No.48, Smash Hits calling it “the oddball single to end all oddball singles”. EMI, nixing a 12-inch, and being hyper-critical according to video director Paul Henry, hardly helped.

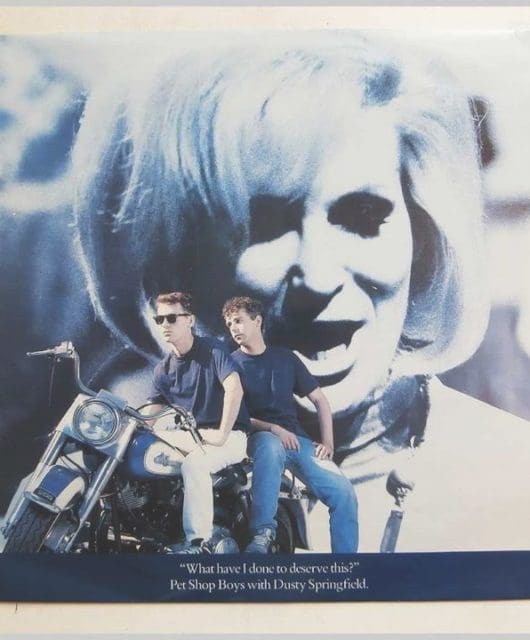

The Dreaming followed that September. It’s cover, taken by brother John Carder Bush at the family’s East Wickham farm home, depicted Bush as a glamorously-coiffured, Houndstooth-attired Mrs Houdini, passing her escapologist husband a key with a kiss. Sepia-tinted to look period, it was romantic but full of that crawling, Gothic ivy’s dark spaces, a scene redolent of Bush’s beloved painting, John Millais ‘A Huguenot’.

Applauded roundly by critics, from Melody Maker to Smash Hits, for its bravery, The Dreaming sold less than predecessors, but still hit No.3, a triumph for such an uncompromising record. Her fingers were firmly on modern music’s pulse. Tapping into technology, weaving jazz, folk, world and classical into a ‘human, emotional’ record. She’d set out to ‘apply the “future to nostalgia”, the result was shot through with early-80s pop’s wild audacity.

It may have been, as Bush puts it “my ‘she’s gone mad, she’s not commercial any more’” album but it got her glowing, in-depth reviews stateside. One from Record’s Nick Burton predicted imminent US stardom. A third single, There Goes A Tenner, failed to chart altogether, its B-side, Ne T’enfuis Pas, predicted the ‘sunnier places’ Hounds Of Love would take her to.

Promoting that hugely successful album in 1985 Bush still singled out The Dreaming as her personal favourite (Big Boi, Bjork and John Lydon agree). With its songs of imprisonment, escape and transformation, this was where she broke free of pop’s expectations and became one of its great outliers. Whether travelling into the heart of geo-political darkness or the depths of the human soul, The Dreaming is a truly Gothic masterpiece.

Read more: Top pop songs of 1981

Read more: Top pop songs of 1982

Kate Bush: The Dreaming – the songs

Sat In Your Lap

Inspired by Stevie Wonder’s Wembley Arena concerts, this brass-blaring, drum-pounding curtain raiser is The Dreaming’s mission statement. Compressed into its three and a half minute stampede are tribal post-punk, prog and an operatic chorus finale. It’s a quagmire of philosophy; seeking/demanding knowledge and enlightenment, quickly realising in Bush’s words “the more you discover, the less you know”. No wonder she imagined singing it as “the king in his castle, the fool on the hill”.

There Goes A Tenner

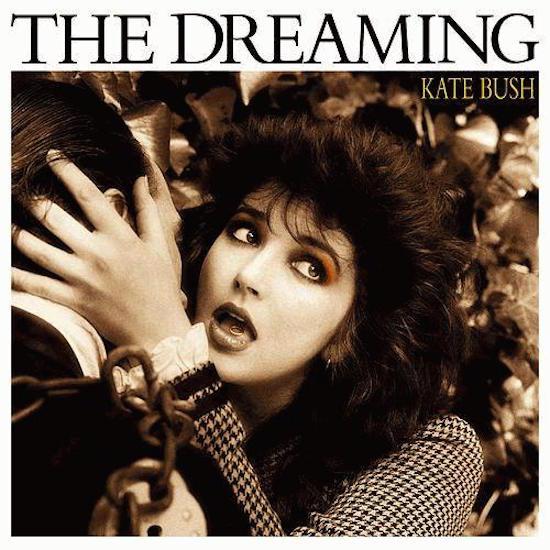

This crime caper about bank robbers is full of unexpected twists. Initially the breathless piano-led verses evoke Ealing comedy/music hall. But as ‘everyone freaks out’ film noir creeps in. The robbers impersonate doomed silver-screen gangsters, Bush’s exaggerated cockney keeps slipping into sadness, then speeding up. The pace drops to a slo-mo chorus, eerily sound-tracked by Dave Lawson’s Synclavier (1982 also disrupting the ‘very 1930s’ atmosphere with that CS80 brass). By the finale, the imprisoned robber’s wistfully recalling a simpler time and you’re left not chuckling but haunted, like Smash Hits’ Neil Tennant. A great ‘lost’ 45 about hard times breeding hapless thieves or Bush studio fright? File next to Buggles retro-futurism.

Pull Out The Pin

Bush is a Vietcong soldier with a silver Buddha, stalking her US enemy in this grotesque beauty. Inspired by a Vietnam war doc, Bush described the song cinematically. The “sweaty jungle” is “shot with sound”; Apocalypse Now-style helicopters, and crickets and frogs. Danny Thompson’s bass strings bend like bamboo, Brian Bath’s clanging guitar is the American’s transistor. Bush gets top-billing, sensuously prowling, then unleashing a ravaged, Breathing-style rasp as war’s true horror sinks in.

Suspended In Gaffa

This surreal waltz (and euro-single) goes down the same rabbit hole as Sat In Your Lap. It’s about seeing a glimpse of God and having to work hard to see him again. Ideas plucked from a Catholic education echo the purgatory of making The Dreaming, Bush chasing flashes of inspiration. If the verses’ piano-led oompah are the breathless search, the heavenly chorus is when God (and the musically sublime) approaches. Even on The Dreaming’s most buoyant moment, anguish meets ecstasy (shrieks piercing the Synclavier haze). That “girl in the mirror” is Bush but she’s also possibly Tennyson’s The Lady of Shalott, weaving tapestries from reflective surfaces, not real life.

Leave it Open

Melodically simple, sonically stunning, philosophically dense. People are “receptive vessels” who should open/close to good/bad. But there’s “harm” within too that needs controlling. Over boot-stomping art-rock are babbling voices. The lead vocal’s heavily flanged like a caged bird beating its wings, another pitch-shifted Bush responds (sonic shorthand for madness, from Bush’s first single-purchase Napoleon XIV to Bowie’s All the Madmen). Leave It Open’s menacing (Lennon-triggering guns, Gabriel/Intruder-style drum explosions) but it summons good spirits as it exorcises bad ones. The key’s in that chant: learned backwards, recorded, then reversed so the original line’s warmly enveloping – just “let the weirdness in”.

The Dreaming

Celebrates the aboriginal outback while dramatising the white man’s invasion. The Dreaming’s full of strange collisions. The ‘earthy’ didgeridoo and deep, tribal rhythms clash with Fairlight machinery, just like the kangaroo thud on the van’s bonnet. Eccentricity veils natural poetry. Sadness too as the displaced race succumbs to alcoholism, it’s in the sonic details, that howling wind’s the men with the diggers. Hope glimmers with birds escaping across the stereo image as a voice mutters a line from aboriginal folk song, Aeroplane.

Night Of The Swallow

Bush is both female lover/male pilot in this classic noir melodrama. He’s embarking on an illegal flight (another risk-taker on a risk-taking album), she’s urging him not to. Her piano-led, moonlit anguish, twists into his illicit take-off, with the chorus flying on wings of penny whistles, bouzoukis, pipes and fiddles. It’s rooted in what brother John Carder calls the Bushes’ “Anglo-Irish mish-mash”, almost cutting between England and wild, glamorous Ireland. This intensely moving song’s seeds were perhaps sown the first time Bush heard those Uilleann pipes (“a stone rippling in my emotional well”).

All The Love

“A lack of love song”, about not expressing love out of fear or pride, and realising it too late. Through the symphonic regret Bush is “at the gates alone” with her piano (heaven’s or school’s? Regardless, it’s inarguably solitary). Everything’s lonely in the stereo space: Palmer’s forlorn bass, percussive rattles (or shutting Venetian blind samples?), heavy sighs and a plaintive choirboy. There are spooky Fairlights too but the climactic farewell message are the real ghosts in the (answer) machine.

Houdini

Like Wuthering Heights, it’s a beyond-the-grave romance. Tough to compose (“it nearly killed me”), Bush’s performance as Mrs Houdini contacting her deceased husband via a medium is frighteningly immersive. More cinematic sound – the clockwork refrain – rhythm’s a flashback to Mrs Houdini watching Harry’s daredevil feats. Houdini’s a multi-tiered structure, a transfigured power ballad boasting ECM bass maestro Eberhard Weber. A Gregorian chorus fill that song’s spaces, Houdini’s swell with strings, sweeping without pop’s usual sweetenings.

Get Out Of My House

The Dreaming’s shrieking, shuddering finale. Inspired by Stephen King’s The Shining, though Ridley Scott’s Alien and A.L. Lloyd’s Two Magicians also feature in this horror-song. Set to slamming-door drums, Bush scream-sings as a wounded soul-as-bolted-house that’s plagued with a trespasser. Like the best horror, it’s deeply sad (and slightly funny). Hounds Of Love embraced love’s ‘licky beast’. Here the heroine turns into a braying donkey to fend off her similarly shape-shifting pursuer. Scour sci-fi master Isaac Asimov’s Foundation or (Bush fave) Pinocchio’s Pleasure Island for clues as to what that mule meant. It could be Bush ‘stubbornly’ realising her vision. Some saw the song as a staged retreat from media intrusion. But on an album about ‘how terribly cruel we are to one another’, it’s really about the maddening fear of getting caught in another’s clutches, be it love-hound or sharp-clawed monster.

Read more: Prefab Sprout albums – the complete guide

Check out the official Kate Bush website